graph TD

title([Government funded healthcare]) --- F[Is coverage mandatory?]

F -->|yes| hf1[Government schemes and \n compulsory prepaid schemes\n<b>HF.1</b>\n]

hf1 --> d[Is entitlement based \n on contribution?]

F -->|no| b[Voluntary private insurance \n Out-of-pocket pay]

d -->|no| h[Government scheme\n<b>HF.1.1</b>]

h --> central[Central government\n<b>HF.1.1.1</b>]

h --> regional[Regional/local government\n<b>HF.1.1.2</b>]

d -->|yes| u[Compulsory prepaid schemes]

u --> pooling[Is there interpersonal pooling?]

pooling -->|yes| compcontr[Compulsory contributory \n schemes \n <b>HF.1.2</b>]

compcontr --> policy[Is insurance\npolicy purchased?]

policy -->|no| shi["Social health insurance \n <b>HF.1.2.1</b>"]

policy -->|yes| comppri[Compulsory private insurance \n <b>HF.1.2.2</b>]

pooling -->|no| cmsa[Compulsory medical \n savings accounts \n <b>HF.1.3</b>]

b --> c[Is prepaid contribution \n required?]

c -->|yes| e[Prepaid\n<b>HF.2</b>]

f -->|yes| vol[Voluntary health insurance\n<b>HF.2.1</b>]

f -->|no| ent[Enterprises schemes \n Non-profit institutions]

c -->|no| oop[Household out-of-pocket expenditure\n<b>HF.3</b>]

oop --> cop[Copayments, user fees]

oop --> cs["Is cost-sharing available\n(compulsory or voluntary)?"]

cs -->|no| oop2[Out-of-pocket pay\n<b>HF.3.1</b>]

cs -->|yes| ccs[Voluntary health insurance \n Compulsory cost sharing\n<b>HF.3.2</b>]

e --> f[Entitlement based on contribution?]

ent --> char[Does the programme run \n for charity purposes?]

char -->|yes| nonpr[Non-profit institutions\n<b>HF.2.2</b>]

char -->|no| pr[Enterprises schemes\n<b>HF.2.3</b>]

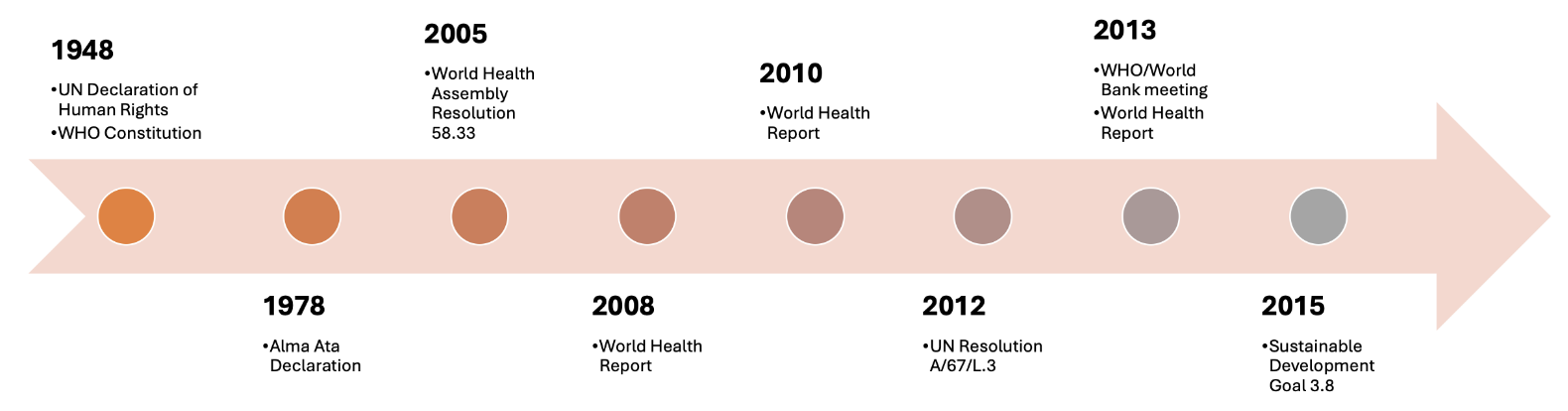

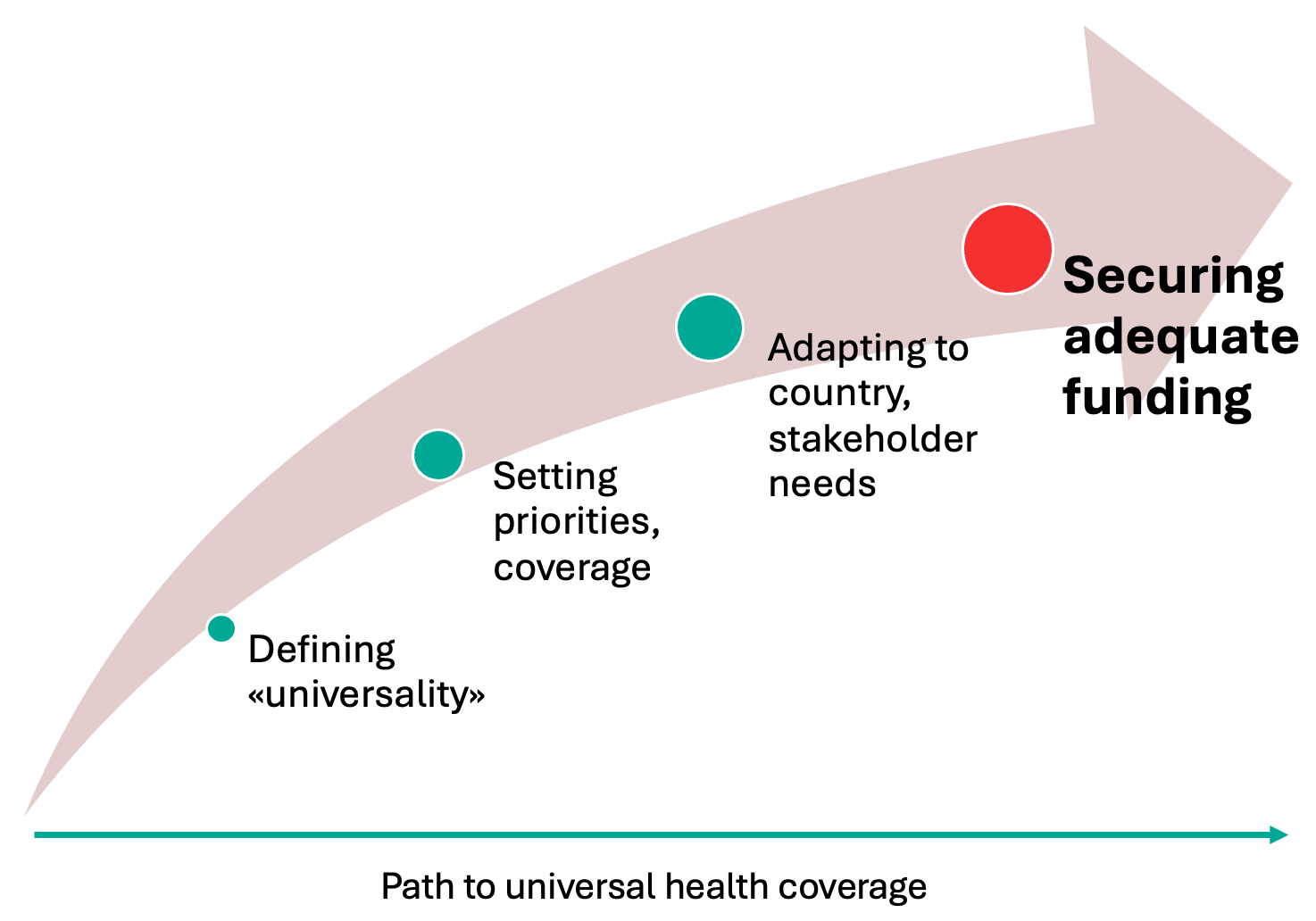

On the path toward universal health coverage (UHC), securing adequate funding represents a key contributor to successful implementation (Figure 1). Funding influences the priority setting and breadth of coverage while reflecting the needs of several stakeholders. Various strategies have been proposed to fund healthcare, which fall into two main categories: tax-based and social health insurance (SHI)-based funding. In the present essay, I will 1) compare the design and main features of tax- and SHI-based funding schemes, 2) critically appraise their key differences, and 3) evaluate their performance under the UHC framework, with an emphasis on applied real-world examples of the use of resources, equity, and resilience.

Funding strategies: structural and organizational features

Healthcare financing schemes are defined as «structural components of healthcare financing systems […] through which people obtain health services» (1). Tax-based systems are government-funded schemes in which entitlement is typically granted to all citizens of a particular country. SHI systems, instead, are classified as compulsory contributory schemes in which health insurance policies are purchased by individuals.

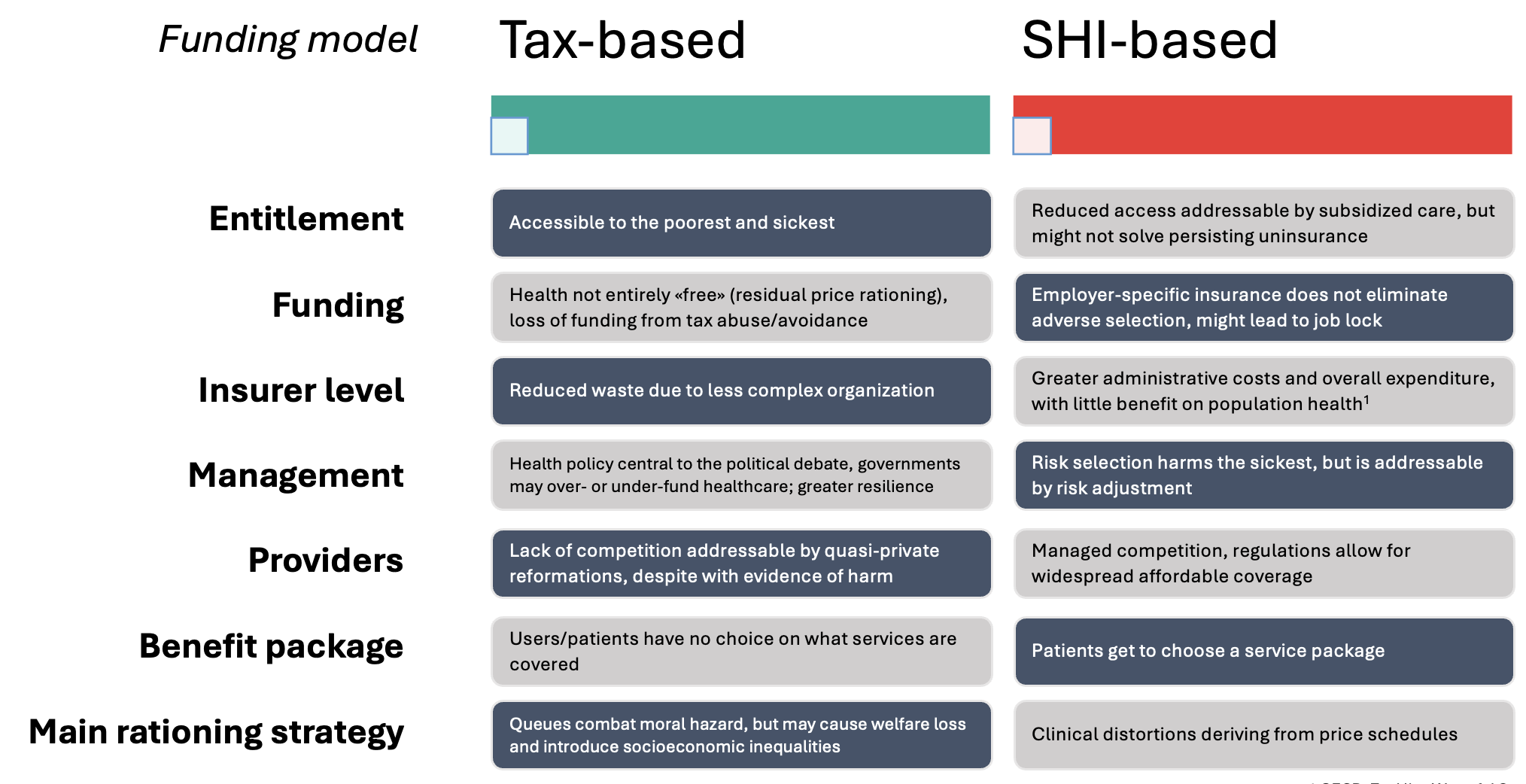

Although in both types some form of non-risk-related contribution is mandatory, tax- and SHI-based financing schemes differ in several aspects (2) (Figure 2). In tax-based systems, money is raised through public revenue by the state and administered by the central or regional government. Hospitals and other providers are publicly owned, and the final user does not get to choose options for coverage. In these systems, shortages (e.g. in staff or resources) lead to queues. In SHI schemes instead, entitlement is based on contribution; money is raised by workers, and the insurers are linked to employers. One or multiple sickness funds manage the healthcare budget, which is typically distributed to privately-owned providers, which offer multiple explicit packages. Rationing occurs by increasing prices.

While the two funding models may appear truly dissimilar, their implementation varies greatly, so that among countries adopting seemingly identical schemes, major distinctions would be observed. Even when not considering such heterogeneity in real-world implementation, inherent structural and organizational characteristics of tax- and SHI-based systems result in fundamental differences (2,3) concerning outcomes and healthcare delivery. Six main areas of differentiation will be discussed.

1. Entitlement

In tax-based systems, entitlement is typically universal and defined by law (1), as in the United Kingdom, Canada, or Italy; when universality is not mandated, programs are arranged to provide healthcare financing to certain segments of the population, as happens with the Medicaid program in the United States, or to tackle specific public health issues, as with the National Tuberculosis elimination programme in India.

In SHI systems, entitlement is contributory by law, either for all citizens or for certain groups. SHI schemes, however, can achieve accessibility by providing subsidized care, despite evidence of persisting uninsurance in these systems (4). Tax-based systems predictably achieve better accessibility, especially for the poorest and sickest segments of the population.

2. Funding

In tax-based systems, health is not entirely free – as residual price rationing typically occurs. Additionally, tax abuse or avoidance can threaten the sustainability of these systems, which may be of serious concern in countries with a limited budget for healthcare.

SHI systems also have their drawbacks. Having employer-sponsored health insurance has been linked to job lock (5), where individuals fear losing their insurance and avoid moving jobs or retiring. SHI is also vulnerable to adverse selection (2), possibly leading to sustainability issues in the long term.

3. Insurers

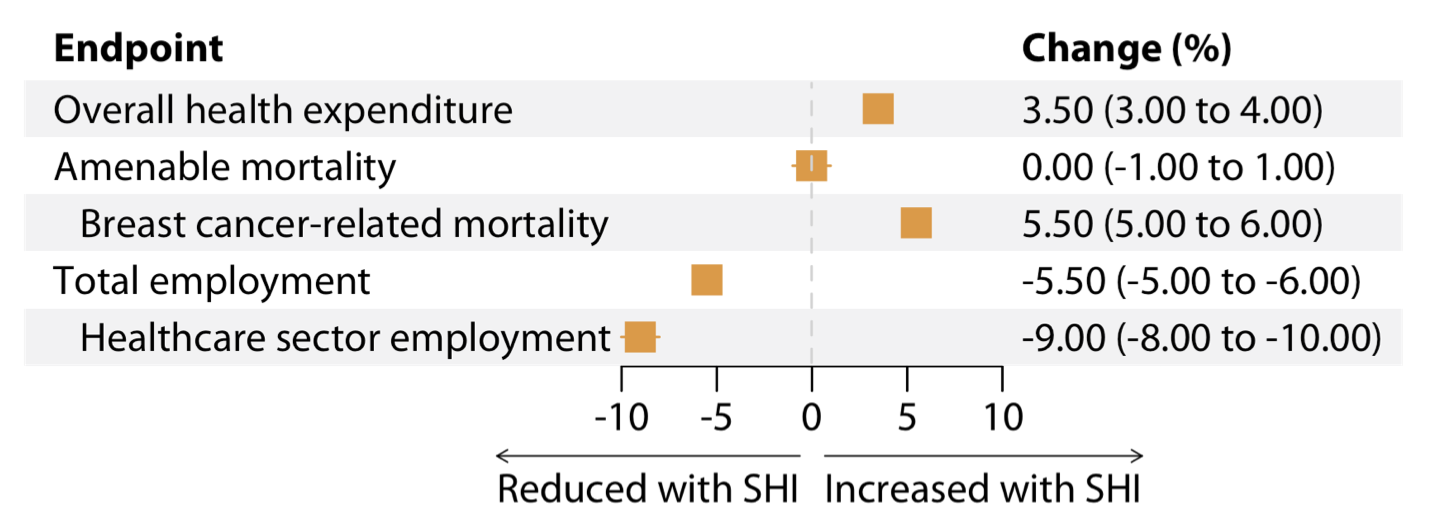

In SHI-based countries where multiple agents are at play, higher expenditure is reported. Since providers in these countries operate for profit, they charge more for services, despite providing coverage to fewer people. Additionally, administrative decentralization leads to higher expenditure (6). It follows that SHI countries where a single insurance fund dominates have an administrative expenditure that is comparable to countries where tax revenues are the major financing source (6). When paralleled with SHI systems, due to a simpler organizational structure, tax-based systems have historically achieved reduced healthcare expenditure and waste (6).

Wasteful expenditure due to poor implementation of the priority setting and inefficient administration amounts to ~20% of the healthcare budget in OECD countries, and up to 40% in developing countries (7); among OECD countries, SHI systems waste significantly more (6). As a result, SHI-based countries have larger healthcare expenditures, but their population does not benefit in terms of overall health and lifespan (8) . Among OECD countries, eight countries achieve high life expectancy while keeping health expenditure comparably low (9) . In six of these (Spain, Italy, Israel, Portugal, Chile, and Costa Rica), healthcare is funded majorly by tax revenue. The remaining two countries (Korea and Slovenia) use mixed funding sources of SHI and tax revenue, possibly hinting that even running a government-based scheme in parallel to an SHI scheme may help to reduce healthcare expenditure without sacrificing outcome.

4. Management

As money is collected through public revenue in tax-financed systems, these countries face almost incessant political debate on healthcare spending. This is the case in countries like Italy (10,11) and the UK (12,13), where political decisions such as increased decentralization and Brexit affected healthcare system performance in the last decade, particularly by hampering workforce planning; this is often tackled by hiring agency workers at the expense of quality of care and reliability (11,14,15). Tax-funded schemes in Europe have also been criticized for their inert bureaucracy (16) that appears resistant to the «information revolution» and has caused delays in the adoption of novel technologies and services. However, the political discourse around healthcare has also demonstrated the potential to improve public participation; in Thailand, where three-quarters of the population receive UHC through a tax-based fund (1), participatory governance through consistent citizen involvement led to improved access to quality care (17).

5. Providers

In tax-based systems, little competition is present between providers (2), which may be seen as a disadvantage over SHI-funded schemes, where the regulations on competition may allow for widespread, affordable coverage. However, there is evidence that aiming for increased competition may affect population health in unexpected ways. In 1991, the UK NHS was the subject of a reform aimed at increasing provider efficiency, the «NHS internal market». In this system, hospitals were encouraged to reduce waiting times and overall price-for-service. This was later shown to have a detrimental effect on the health outcomes of patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction (18). Quasi-private reforms are thus seen as ineffective and reduced competition may be seen as a structural feature of tax-based systems.

6. Rationing

In tax-based systems, staff or resource shortages introduce queues, which are seen negatively by the general public and may consequently take a central stage in the country’s political debate. Additionally, queues are shown to exacerbate existing socioeconomic inequalities by rendering healthcare less accessible to the poor and sickest (19). On the other hand, in SHI-based countries, queues are not a major issue, and health policy aims to control the larger healthcare spending. To do so, price schedules are utilized, although these may produce clinical distortions by inducing or aggravating a prominence effect (20) on physicians.

Other challenges

Resilience

The 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have affected healthcare systems worldwide (9,30). Under stressful circumstances, resilient health systems maintain performance and prevent individual financial hardship while minimizing service disruptions and system costs. This is achieved through preparedness and dynamic adaptation (31). In comparison with pre-pandemic years, government-based schemes in OECD countries increased healthcare expenditure by an average of 26% per year in 2019-2021 (9). Spending growth was greater in countries with SHI (9), possibly because in these countries, governments with limited purchasing roles in healthcare had to shoulder significant responsibilities during the pandemic.

Even SHI-based countries with apparently strong healthcare systems were less resilient during the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic (32). This resulted from more fluctuating, economy-dependent service coverage, which mostly affected the poorer segments of society – again, in contrast with the UHC principle to protect the poor and sickest. As a result, these countries have suffered greater social pressure, morbidity, and mortality (31). However, it should be noted that funding is only one of several determinants of health system resilience (33), which also include effective governance, health service delivery, workforce, public health function, and technologies, along with achieving community engagement.

Inclusivity

In 2010, more than 3 percent of the world’s population incurred catastrophic health spending (29). In an analysis of 133 countries, catastrophic spending occurred more frequently in SHI-based systems than in tax-based systems, despite increased health expenditure in the former (29). The authors stated that to protect people from catastrophic out-of-pocket payments, what is needed is to increase «the share of total health expenditure that is prepaid», especially «through taxes and mandatory contributions». In other words, to shift towards tax-funded health systems would lead to broader coverage and better population health (24).

Is tax-based funding better?

The main challenge in appraising the respective advantages and drawbacks of tax- and SHI-based funding schemes lies in the fact that no single country perfectly embodies a model; rather, each country adapted the models developed by Bismarck and Beveridge to their own needs. Ultimately, the dichotomization of healthcare funding schemes appears simplistic and forced (Figure 5). Each country’s approach to health policy reflects social and cultural values other than economic interests alone (34). Another layer of complexity lies in transitions from one scheme to another over time, which may be informative from an experimental point of view but may also obfuscate judgment on a country’s healthcare performance in time. Additionally, the literature on the subject is observational and mainly relies on self-reported country estimates and statistics, which are prone to error. Unaccounted residual confounding is likely even in analyses reported by large consortia, such as the OECD. No two countries have perfectly similar population demographics and burdens of disease, and to what extent the incidence of a disease is a cause – or consequence – of health policy is largely undetermined.

Conclusion

Given the recent slowdown in UHC progress, greater, focused international efforts in policy-making are warranted to adapt to aging, increasingly morbid populations. In countries with tax-based healthcare funding, budgetary pressure and discourse dominate the stage of political discussion, and tax abuse is a serious threat to population health. Governments can leverage funding as needed, and the population benefits from participatory governance and resilience. While they may not be faultless, tax-based systems are significantly less expensive, and more equitable, inclusive, and resilient. The wider adoption of prepaid contributions under a tax-based healthcare financing framework appears justified.